Zero-commission trading became increasingly popular with fintech apps and eventually migrated to the mainstream online brokers. The notion of paying no commissions on trades appealed to the masses as evidenced by the parabolic growth of the client-bases of certain fintech companies. What appears to be a win/win situation on the surface gets murky when factoring in payment for order flow agreements beneath the surface. Traders should be aware of the potential impacts these pre-arranged deals may have on their trades.

What Is Payment For Order Flow?

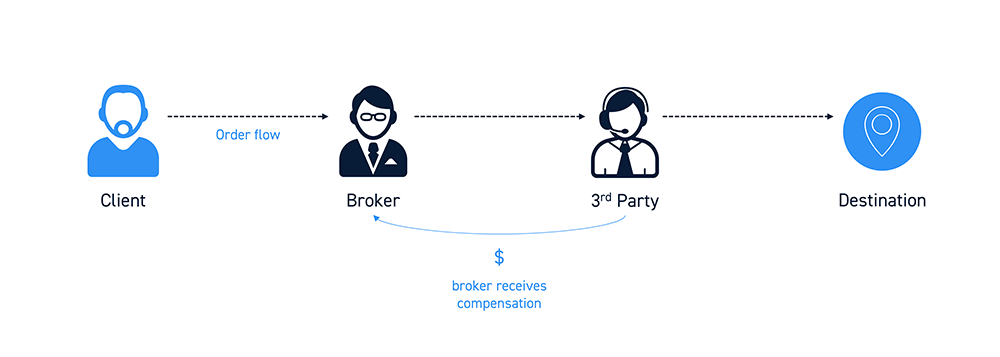

Think of order flow as traffic in a big city. The orders are cars and the destination is the market. Naturally, everyone wants to get to their destination first.

When brokerage clients place their trade orders, the broker should try to direct that traffic through the most optimal and efficient route to get to the destination, allowing the trade to be executed in the quickest manner at the most efficient fill.

Unfortunately, an order flow agreement may commit the broker to direct traffic to a prearranged third-party route to reach the destination. The third party compensates the broker for sending additional traffic their way, which benefits the broker (often at the expense of the client)

Many retail brokerage customers are unaware of this process since they are primarily focused on long-term, passive investing strategies, however traders will be sensitive to the negative consequences.

This process is legal when managed within the SEC’s guidelines. The SEC rule 606 requires all brokers disclose the presence of order flow agreements to customers and update their data through filing disclosures that specify who they received order flow payments from and how much. Many brokers will “spin” the cost savings and “price improvements” they pass down to their customers as a result of order flow agreements.

Who Pays For Order Flow And Why?

Liquidity attracts liquidity. This is a key facet to keep in mind. There are four types of third-parties willing to pay for order flow:

Wholesalers are electronic trading BDs utilizing high frequency trading, algorithmic and low latency trading programs to carry out order executions. These firms use speed and access to split spreads down to the 10,000ths of a penny to capitalize on order flow liquidity. These firms account for nearly 20-percent of all daily trading activity.

Market makers compete with each other for optimal executions for clients. They are responsible for using firm capital to take the risk on both sides of the spread and profiting from the spread. However, order flow arrangements empower market makers with the additional liquidity to bundle large orders, deal from inventory and take the opposite sides of trades to buffer exposure risk.

Exchanges will pay for order flow to promote itself and galvanize its reputations as a source of liquidity for institutional clients, listed companies and companies seeking to IPO. Order flow may get directed to the floor specialists that take on the role of a stock’s single market maker or to the exchange owned alternate trading systems (ATS) which include some of the most popular ECNs like NYSE ARCA, CBOE EDGX and various dark pools.

Institutions may pay for order flow to bundle and arbitrage large block orders while still adhering to the National Best Bid Offer (NBBO) parameters. These entities are paying for liquidity to fill their own trades rather than outsource to liquidity providers.

How Third-Parties Profit From Order Flow

Retail brokers make fees from third-party payers usually based on a per-share or per-dollar amount traded arrangement. So how do these third-party order flow buyers make money?

There are various ways profits are attained with order flow liquidity.

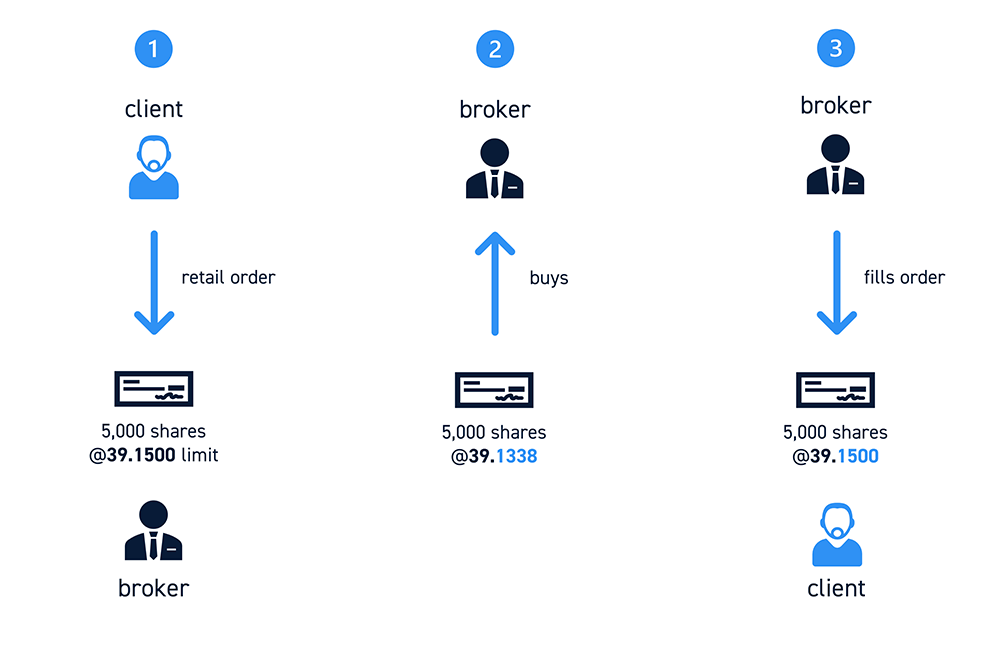

Third parties can bundle retail orders and front run them (i.e. retail order to buy 5,000 shares XYZ at 39.15 limit, firm buys 5,000 shares average 39.1338 and fills the 39.15 limit order).

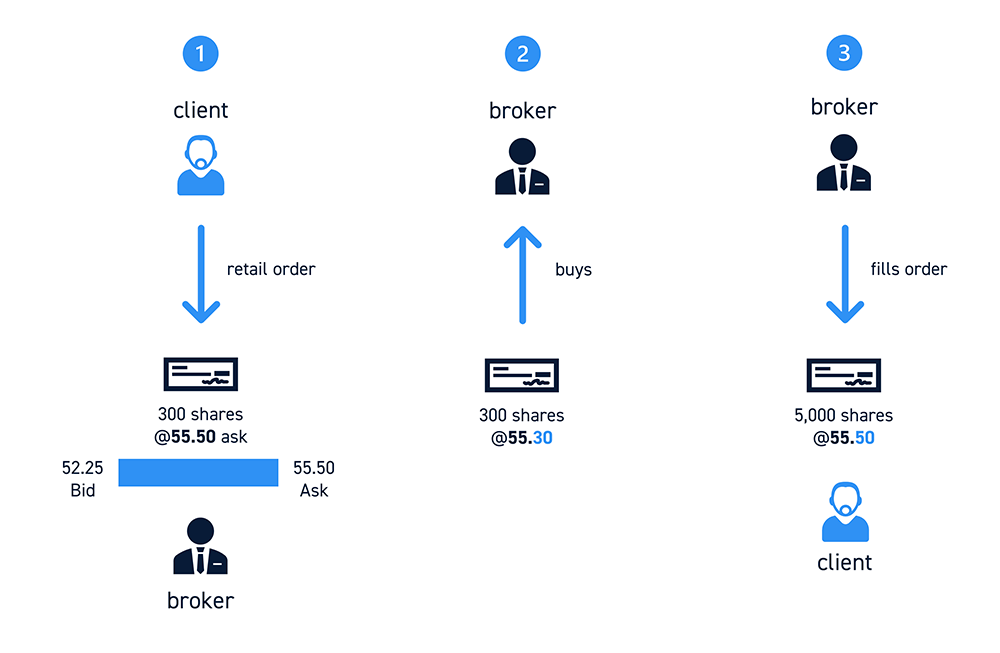

They can arbitrage the spreads (i.e. retail order to buy 300 XYZ at 55.50 ask during a 55.25 x 55.50 wide bid/ask spread, firm buys at 55.30 and sells to retailer at 55.50).

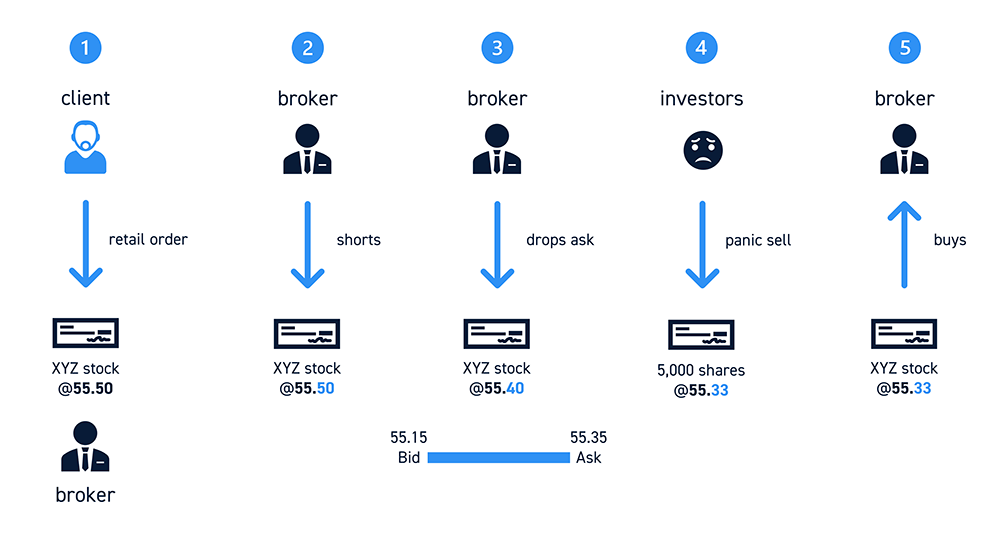

They can trade against the retail order (i.e. firm shorts XYZ at 55.50 to execute retail buy order at 55.50, then pulls bids and drops ask to 55.40 driving prices down to 55.15 x 55.35 bid/ask to cover the trade at 55.33 from panic sellers).

These are examples with limit orders. Market orders are the most profitable as third parties can really capitalize on the 10,000ths of a penny per 0.01 spread. Third parties can also receive additional kickbacks with their own order flow agreements with dark pools, ATS and ECNs.

Is It Legal To Receive Payment For Order Flow?

For the time being, payment for order flow agreements are legal as long as they are disclosed and updated quarterly. There is much controversy about the ramifications of order flow arrangements.

Brokers argue these arrangements lower trading costs as they pass the savings on to their customers. They also claim customers received price improvement with these arrangements.

Pundits argue order flow payments actually hurt the natural flow of markets and present too many opportunities to capitalize on inefficiencies of wide spreads, market orders and stifled transparency. Incidentally, the U.K. Financial Authority found the conflict of interest so overwhelming that they banned the practice of payments for order flow in 2012.

The Cost to Traders

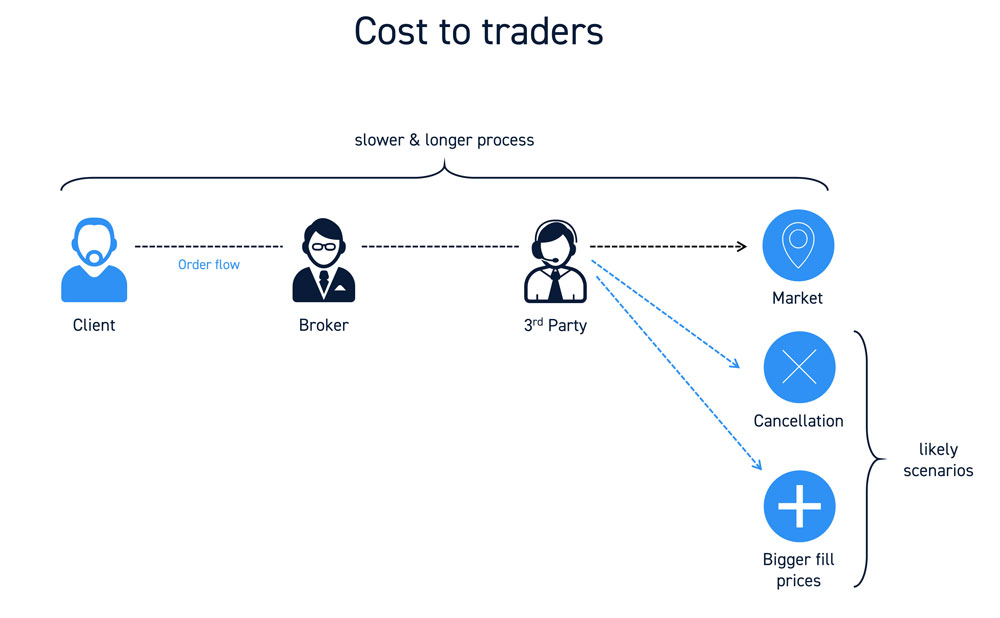

While retail investors may not notice or care about the ramifications of order flow agreements, active traders should be aware of the material effects and indirect costs.

With order flow arrangements, traders have no control over how their orders are routed and can expect to run into issues trying to execute larger sized trades. Often times, larger sized limit orders won’t get filled quickly or completely unless the market maker knows there are large seller orders in his book. At that point, you can expect to get filled as the bids drop afterwards.

Third parties often trade against your order, meaning you get filled on the long position moments before the price collapses or wiggles lower. This is such a common occurrence that traders are often convinced stocks will drop as soon as they make their entry and thus hesitate until FOMO (fear of missing out) prompts them to chase an entry at the top.

Executions are slower to fill (due to being passed through a middleman) if they fill completely. This can result in constant cancelled orders which may frustrate traders to the point of chasing prices to get a fill or even placing market orders. Larger sized orders can be expected to show up on level 2 which can further push prices away and again cause the trader to cancel and chase fills. This is particularly damaging in fast moving volatile markets and stocks with wide spreads.

How To Take Control Of Your Order Flow

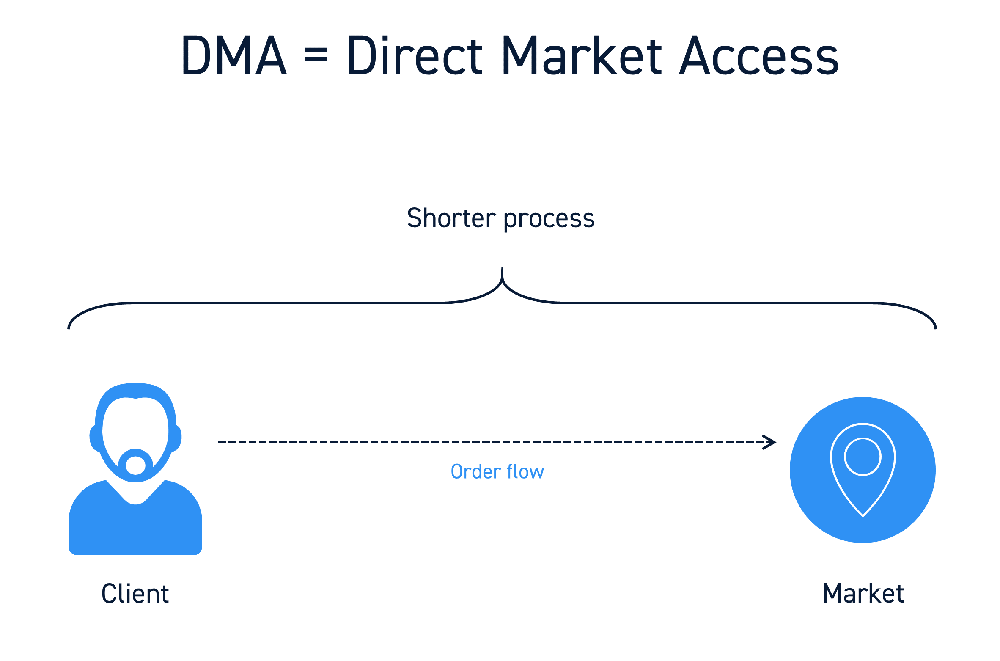

Using a direct market access (DMA) broker enables traders to specify their own order routes for instantaneous and direct executions.

Earlier, we compared order flow to traffic. Direct routing is like taking an empty toll road bypassing bumper to bumper traffic in rush hour. While there are passthrough fees for taking liquidity, there are also rebates for providing liquidity. Momentum traders can usually buy on the ask (taking liquidity) with a direct routing order to an ECN and then sell on the inside ask to collect a rebate (providing liquidity) on their exits.

DMA trading platforms provide robust unclogged data and structural stability which are paramount during period of extreme market volatility. This is evidenced by the helpless customers locked out of their zero-commission fintech brokerage accounts from hours to days during the most volatile stock market activity in history during 2020.

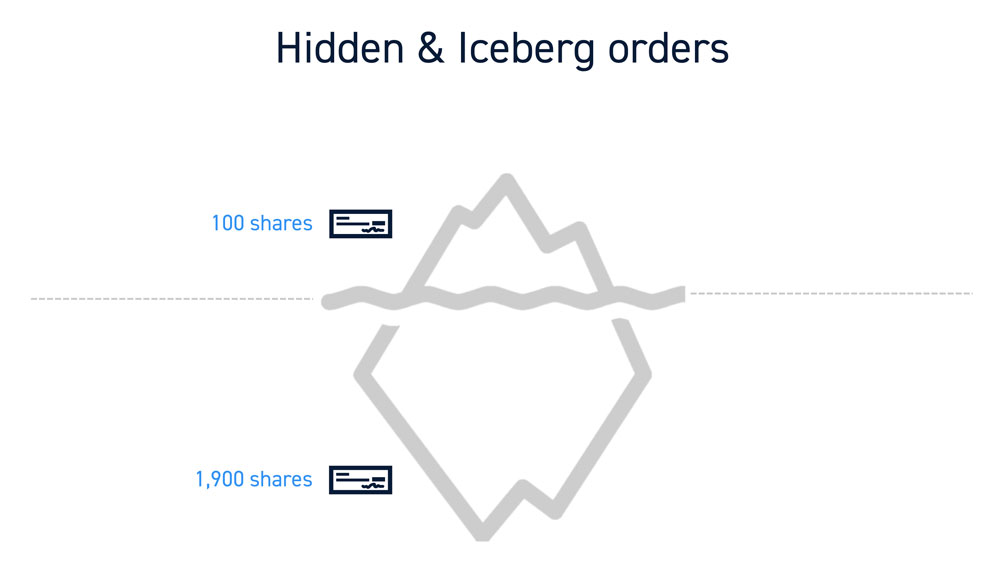

Hidden And Iceberg Orders

One of the most beneficial aspects of DMA brokers is the ability to place hidden (invisible on level 2) and iceberg orders (IE: display 100 shares on the ask but selling 2,000 shares) through ECN limit books. These allow traders to mask their true share size (transparency) so as not to disrupt momentum and push prices away.

For example, Trader A places an order to sell 5,000 shares of XYZ on the bid through an order flow broker. He gets filled for 300 shares and the remaining 4,700 shares now sit on the inside ask. This triggers panic as the bids quickly drop lower and more sellers step in front of his limit ask price. Trader A panics and keeps cancelling and lower his limit order only to get partial fills until he finally throws in the towel with a market order which fills him much lower before a snap back bounce.

On the other hand, Trader B using a DMA broker places a hidden order to sell 500 shares between the bid/ask spread getting filled without disturbing the momentum as prices continue higher. Trader B methodically monitors the time and sales with level 2 to place hidden and iceberg orders into the grind until a volume spike enables him to close out the rest of the 5,000-share position before the quick reversion pullback. These are not uncommon situations. They illustrate how traders need to have the tools to capitalize on market inefficiencies, rather than fall victim to them.